The story of Dagbon before Naa Gbewaa remains one of West Africa’s most overlooked historical narratives. While royal chronicles celebrate the achievements of kings and chiefs, the deeper origins of Dagbon lie buried in oral traditions, ancestral memories, and the lives of people who inhabited these lands long before centralized rule emerged.

Understanding Dagbon before Naa Gbewaa requires us to look beyond palace walls and royal genealogies. It demands that we listen to the whispers of elders, the rhythms of ancient drums, and the stories of aboriginal communities whose contributions shaped the kingdom we know today.

This comprehensive exploration uncovers the forgotten foundations of Dagbon before Naa Gbewaa—revealing how settlements, spiritual systems, and early migrations created the bedrock upon which kingship would later be built.

Table of Contents

- Why History Cannot Begin With Kings

- The Land Before Dagbon Had a Name

- The Aboriginal Dagbamba: First Settlers

- The Tiyawumya: Giants in Ancient Memory

- How Society Functioned Before Kingship

- Migration Waves That Shaped Early Dagbon

- The Emergence of Centralized Order

- Why These Forgotten Stories Matter Today

Why History Cannot Begin With Kings

Most narratives about Dagbon before Naa Gbewaa start with royal lineages, creating a false impression that Dagbon was empty or silent before kingship arrived. This approach erases centuries of life, culture, and organization that existed long before any chief sat on a skin.

Dagbon before Naa Gbewaa had settlements, families, spiritual leaders, and complex social structures. The land knew cultivation, trade, and governance—just not in the centralized form that would emerge later with royal authority.

Starting history exclusively from Naa Gbewaa suggests that everything before him lacked value or legitimacy. This narrative omission creates dangerous gaps in understanding. It makes kingship appear as the creator of order rather than what it truly was: a new political system built upon ancient foundations.

The early history of Dagbon lives primarily in oral tradition. Court drummers, elders, and lineage keepers preserved these memories through praise names, proverbs, and ceremonial recitations. These oral archives carry knowledge that written records cannot capture—the texture of daily life, spiritual beliefs, and communal values that defined society.

Without acknowledging Dagbon before Naa Gbewaa, we lose essential context for understanding how the kingdom actually developed. We miss the contributions of land custodians, earth priests, and aboriginal settlers whose presence made later centralization possible.

The Land Before Dagbon Had a Name

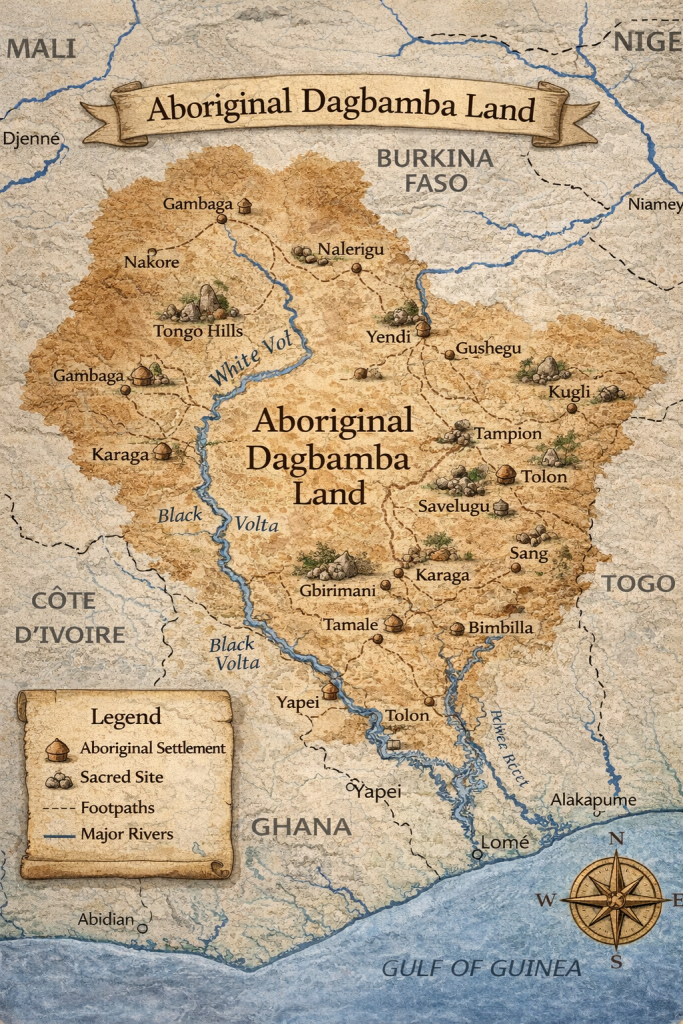

Before Dagbon before Naa Gbewaa became a kingdom with defined boundaries, the territory existed as a landscape of rivers, plains, forests, and valleys. These geographical features were not empty spaces awaiting rulers—they were living environments already inhabited and understood by settled communities.

The origins of Dagbon Kingdom begin with the land itself. Early inhabitants organized their lives around water sources and fertile soil. Rivers provided fish and drinking water. Forests offered medicinal herbs, wild fruits, and game animals. Open plains became farmland where millet, yams, and groundnuts grew according to seasonal rhythms.

Settlement patterns during this period were decentralized. Small communities clustered near resources, forming independent units connected by kinship, trade, and shared customs. These scattered settlements would gradually coalesce into larger networks as population increased and interactions intensified.

The relationship between people and land transcended mere economic utility. Certain locations carried spiritual significance. Sacred groves, ancient trees, and particular rock formations were believed to house ancestral spirits. These sites received ritual attention and protection because disturbing them risked angering powerful forces.

Earth priests served as intermediaries between communities and the land. They performed ceremonies to ensure good harvests, conducted rituals before clearing new farmland, and mediated when land disputes arose. Their authority came from spiritual knowledge rather than political power.

This sacred connection to place explains why understanding Dagbon before Naa Gbewaa requires recognizing that the land shaped society long before kingship emerged. The territory had meaning, memory, and established ways of life that would influence all future developments.

The Aboriginal Dagbamba: First Settlers

The aboriginal Dagbamba history refers to the earliest known inhabitants of the region—people who lived on the land long before royal dynasties and centralized kingdoms appeared. These first settlers created the foundational communities from which Dagbon would eventually emerge.

Unlike later periods dominated by kings and chiefs, the aboriginal Dagbamba organized themselves through kinship networks and community-based leadership. Elders guided decision-making based on wisdom and experience. Authority was earned through knowledge of traditions, farming expertise, and spiritual insight—not inherited through royal bloodlines.

Life revolved around agricultural cycles and cooperative labor. Families worked together during planting and harvest seasons. Neighbors shared tools, seeds, and knowledge. When conflicts arose, community mediation sought restoration of harmony rather than punishment of offenders.

Spiritual practices centered on ancestor veneration and land rituals. The aboriginal Dagbamba maintained shrines where they honored deceased relatives and sought guidance from spiritual forces. These practices created continuity between the living and the dead, reinforcing social cohesion and moral accountability.

It’s crucial to distinguish between these early inhabitants and the ruling groups that arrived later.The pre-Gbewaa Dagbon history shows that modern Dagbamba society emerged through a gradual fusion—a blending of aboriginal communities, incoming ruling families, and various migrant groups who settled in the region over centuries.

These populations did not remain separate. Through intermarriage, cultural exchange, and gradual assimilation, distinct groups became one people. The boundaries between “original settlers” and “later arrivals” dissolved over generations. What bound them together was shared language (Dagbani), common customs, and collective identity rather than single-ancestry claims.

This process of amalgamation is central to understanding how Dagbon began. The kingdom was built by many hands and many histories, not by one family or one heroic founder.

The Tiyawumya: Giants in Ancient Memory

Among the most intriguing elements of Dagbon before Naa Gbewaa are oral traditions about a people called the Tiyawumya (sometimes pronounced Tiawomya). These stories, preserved by elders and drum historians, speak of an ancient population characterized by unusual physical stature and strength.

According to these accounts, the Tiyawumya were extraordinarily tall and powerful—described in terms that suggest giant-like proportions. Elders recount that their bangles were so large a modern person could pass an entire arm through them. Some stories claim their voices carried tremendous distances when they sang or called out.

These descriptions should not be interpreted literally by contemporary standards. Instead, they serve as oral history’s way of marking deep time—indicating that the Tiyawumya belonged to an era vastly different from the present, so ancient that normal human categories barely applied.

The aboriginal Dagbamba history suggests the Tiyawumya eventually disappeared through natural demographic change, migration, or replacement by subsequent generations. Their descendants or the populations that followed them became the early aboriginal communities that later formed the foundation of Dagbon society.

Today, stories of the Tiyawumya are fading from collective memory. Many dismiss them as myths or exaggerations because they lack documentation in written historical records. As Western-style education emphasizes written sources, oral traditions face marginalization. As elders pass away without transmitting these stories to younger generations, invaluable historical knowledge disappears.

Yet myth and memory serve vital functions in African historical reconstruction. Where written records don’t exist—which encompasses most of Africa’s deep past—oral traditions provide the only available evidence for understanding ancient societies. These stories preserve cultural identity, explain long-term changes, and maintain connections to ancestral origins.

The Tiyawumya narrative reminds us that Dagbon before Naa Gbewaa reaches far beyond what written histories document. The kingdom’s roots extend into epochs where oral tradition alone preserves human presence and activity.

How Society Functioned Before Kingship

Understanding Dagbon before Naa Gbewaa requires examining how communities organized themselves before centralized political authority emerged. Contrary to assumptions that pre-kingdom societies were chaotic, early Dagbon maintained order through community-based systems rooted in tradition, kinship, and spiritual authority.

Leadership was distributed and functional rather than concentrated in royal hands. Elders guided communities through their accumulated wisdom and knowledge of customs. Important decisions emerged through discussion and consensus-building, not top-down commands. Authority grew organically from trust and demonstrated competence.

Earth priests and shrine custodians played central roles in this decentralized system. They were responsible for spiritual well-being, performing rituals to honor ancestors, protect communities from spiritual harm, and ensure agricultural fertility. Before any major undertaking—clearing new farmland, resolving serious disputes, or establishing new settlements—spiritual consultation was necessary.

Sacred places received special protection. Certain groves, trees, and water sources were considered dwelling places of spirits. Disturbing these sites without proper ritual could bring misfortune, so communities carefully maintained these spiritual boundaries.

Social organization emphasized cooperation over competition. Farming was collaborative—families and neighbors worked together during labor-intensive periods like planting and harvesting. This mutual assistance created strong social bonds and ensured everyone’s survival.

Conflict resolution focused on restoration rather than punishment. When disputes arose, elders mediated to identify solutions that would restore community harmony. The goal was reconciliation, not victory for one side over another.

Life cycle rituals marked important transitions: birth ceremonies welcomed children into the community, initiation rites moved young people into adulthood, marriages united families, and funeral rites ensured proper passage of the deceased into the ancestral realm. These ceremonies strengthened social cohesion and reminded people of their connections to ancestors and land.

This examination of pre-Gbewaa Dagbon history reveals that kingship did not create order from chaos. It simply reorganized existing systems of authority, building upon foundations that aboriginal communities had already established over generations.

Migration Waves That Shaped Early Dagbon

The early history of Dagbon involves multiple migration waves spanning long periods rather than a single founding journey. Understanding how Dagbon began requires recognizing that different groups arrived at different times for various reasons, each contributing to the eventual formation of Dagbon society.

Some migrations followed environmental factors. Groups moved seeking fertile land, reliable water sources, and favorable farming conditions. Rivers attracted settlements. Areas with good soil and adequate rainfall became population centers.

Other movements resulted from external pressures—conflicts, drought, political upheavals in neighboring regions, or the search for safer territories. These push factors sent populations searching for new homelands where they could establish stable communities.

Settlement was gradual and often peaceful. Newcomers did not always displace earlier inhabitants through conquest. In many cases, they lived alongside existing communities, negotiating for land rights and acceptance. Over time, these separate groups intermarried, shared agricultural knowledge, exchanged cultural practices, and adopted common languages.

This process of assimilation was slow but transformative. People who initially saw themselves as distinct gradually developed shared identity. Children born from intermarriages belonged to both groups. Customs blended. Rituals merged. Languages influenced one another until Dagbani emerged as the common tongue binding diverse populations together.

The origins of Dagbon Kingdom cannot be traced to a single arrival moment or founding ancestor. Instead, Dagbon grew through accumulated migrations, patient adaptation, and centuries of cultural synthesis. Each wave of newcomers added new elements while also accepting and incorporating existing traditions.

This migration history shaped language, customs, and collective identity. Dagbani developed as a linguistic fusion. Farming techniques evolved through knowledge exchange. Social practices combined elements from multiple traditions. Gradually, a shared sense of belonging emerged—a Dagbamba identity that transcended individual lineage claims.

Recognizing these multiple migrations helps us understand Dagbon before Naa Gbewaa as a product of cooperation and adaptation rather than conquest and domination. The kingdom’s strength came from its ability to incorporate diverse populations into a cohesive whole.

The Emergence of Centralized Order

As Dagbon before Naa Gbewaa evolved, changing conditions created pressures for new forms of organization. Population growth, expanded settlements, and increased interactions between communities made the old decentralized systems less effective for managing complex challenges.

Trade routes developed, connecting previously isolated communities. Farming areas expanded as population increased. Conflicts, though still limited, became more difficult to resolve through small family-based mediation. These changes created demand for wider coordination and stronger leadership structures.

When new migrant groups encountered aboriginal populations already living on the land, these meetings weren’t always violent confrontations. Many involved careful negotiation. Newcomers needed land and acceptance. Earlier inhabitants needed peace and stability. Through dialogue, ritual agreements, and recognition of mutual interests, space was created for coexistence.

However, tensions did arise over unclear authority. Questions emerged: Who should lead? Who should protect the community? Who should speak for multiple settlements when dealing with external groups? These uncertainties prompted new organizational experiments.

Alliances formed between families and communities. Strategic marriages joined powerful lineages. Spiritual approval was sought from earth priests and land custodians to legitimize new arrangements. Trust built slowly through demonstrated competence and respect for existing traditions.

From these interactions, a new political concept began taking shape. Leadership started covering wider territories beyond individual villages. Certain families gained recognition for organizing defense, settling disputes between communities, and coordinating relationships with neighboring groups.

This was not yet kingship as Dagbon would know it under Naa Gbewaa and his successors. But these early arrangements laid the groundwork for centralized rule. Authority didn’t appear suddenly from nothing—it grew from existing systems, shaped by negotiation, cooperation, and shared necessity.

The origins of Dagbon Kingdom lie in this transitional period when community-based authority gradually transformed into territorial political organization. The new order built upon the land, the aboriginal people, and the long history that preceded it.

Why These Forgotten Stories Matter Today

Understanding Dagbon before Naa Gbewaa carries profound implications for contemporary identity, unity, and historical accuracy. When history begins only with kings and royal genealogies, it creates dangerous gaps in collective understanding and opens space for confusion about origins and belonging.

Reducing Dagbon’s past exclusively to royal lineages suggests that authority and legitimacy flow from one family alone. This narrow view ignores the aboriginal communities, earth priests, and early settlers whose contributions were essential to society’s survival and development. Such historical erasure weakens truth and creates false hierarchies.

The pre-Gbewaa Dagbon history reveals that modern Dagbamba identity emerged through cooperation, migration, and assimilation—not through single-ancestry claims. Recognizing this shared foundation becomes a powerful tool for unity. When people understand that Dagbon was built by many hands and many histories, it becomes easier to see one another as relatives rather than rivals.

Shared origins encourage mutual respect. They remind everyone that Dagbon’s strength has always come from collective effort and cultural synthesis rather than division and exclusivity. This understanding can reduce unnecessary disputes about who belongs or who has greater claim to Dagbamba identity.

Respecting how Dagbon began also means honoring both landowners and rulers. The land existed before kings, and kingship grew upon it. Earth priests, elders, and shrine custodians safeguarded spiritual and communal well-being while later rulers provided wider political coordination. Both roles were crucial, and neither should be erased from memory.

By holding these multiple histories together—aboriginal settlers, spiritual leaders, migrant groups, and eventual rulers—Dagbon can move forward with clarity, balance, and respect for its deep roots. Understanding Dagbon before Naa Gbewaa provides the complete picture necessary for informed identity and unified purpose.

Recommended Resources:

- African Oral History and Historical Methodology – Academic research on oral tradition preservation

- Pre-Colonial West African Political Systems – Scholarly analysis of decentralized governance

- Internal Link: The Life and Legacy of Naa Gbewaa

- Internal Link: Understanding Dagbamba Culture and Traditions

Conclusion: Dagbon’s Roots Run Deeper Than Royal Skins

Dagbon before Naa Gbewaa reveals a historical landscape far richer and more complex than royal chronicles alone suggest. Long before centralized authority emerged, the land held thriving communities, sophisticated spiritual systems, and organized social structures.

The aboriginal Dagbamba history demonstrates that kingship did not create Dagbon—it arose from a society that already existed. Aboriginal communities, earth priests, and early migrants laid foundations upon which royal rule would later be constructed. Their contributions deserve recognition alongside the achievements of kings and chiefs.

These stories remind us of oral history’s vital role in preserving knowledge that written records cannot capture. Much of Dagbon before Naa Gbewaa lives in elder memories, drum histories, and ancestral recitations. Listening to these voices helps preserve truths that would otherwise disappear as generations pass.

Understanding the early history of Dagbon allows us to appreciate kingship without making it the only story that matters. It creates space for landowners, first settlers, and countless unnamed ancestors who shaped Dagbon long before royal rule emerged.

This exploration closes our examination of Dagbon before Naa Gbewaa and prepares us for the next phase of history: the rise of Naa Gbewaa himself, the establishment of royal skins, and the formation of the centralized kingdom we know today. From these deep foundations, we can better understand how centralized authority grew and why it took the particular form it did.

Dagbon before Naa Gbewaa is not merely prologue to royal history—it is the essential foundation without which the kingdom could never have existed.