The Asante Dagomba War has been taught in classrooms and repeated in history books for generations as a decisive military conquest. According to popular accounts, powerful Asante forces invaded Dagbon, defeated its armies, and reduced the kingdom to a tributary state paying regular homage to Kumasi.

But what if this entire narrative rests on shaky foundations?

When historians examine the actual evidence—oral traditions, Arabic chronicles, political chronology, and institutional records—a radically different picture emerges. The Asante Dagomba war history we’ve been told appears to be largely a colonial-era construction, built on misinterpreted sources and Eurocentric assumptions about African power.

This article re-examines the claim of an Asante conquest of Dagbon using rigorous historical methodology. By testing assertions against dates, reigns, and documented evidence, we’ll discover that the Asante Dagomba war myth collapses when confronted with facts.

How Colonial Historians Created the War Narrative

Colonial Assumptions About African Power

British and European historians approached African societies with rigid preconceptions. In their worldview, political relationships followed clear hierarchies: empires expanded, weaker states were conquered, and tribute flowed from defeated to victor.

African diplomacy, however, operated far more fluidly. Relationships between precolonial states involved trade agreements, military alliances, intermarriage, ritual recognition, and temporary obligations—often existing simultaneously without implying total domination.

Colonial writers struggled to accommodate this complexity. Commercial agreements became “tribute.” Diplomatic leverage became “overlordship.” Failed or limited military expeditions were reinterpreted as conquest.

The Birth of the Conquest Narrative

Once these interpretations entered colonial reports and early academic works, they were cited repeatedly until they hardened into “established fact.” Nuance disappeared, replaced by a simplified story of war and subjugation.

The Asante Dagomba conflict narrative didn’t emerge from Dagbon or Asante historical traditions themselves. It was shaped by colonial lenses imposed on African power dynamics.

The Problematic Sources Behind the Myth

The Kitāb Ghanjā Ambiguity

At the heart of the Asante Dagomba war history lies two sources granted disproportionate authority: the Kitāb Ghanjā (an Arabic chronicle) and Ludwig Ferdinand Rømer’s 18th-century coastal observations.

The Kitāb Ghanjā contains ambiguous place names and internal contradictions. Crucially, it doesn’t clearly name Yendi in the passage cited as proof of Asante invasion. Instead, historians assumed a vague reference (“GhGh”) must point to Dagbon’s capital—despite the text explicitly naming Yendi elsewhere.

This assumption was repeated until it became “fact,” despite lacking certainty.

Rømer’s Account: Defeat Recast as Victory

Rømer’s narrative describes a northern expedition marked by extreme hardship, heavy losses (approximately 40,000 men), occupation of an abandoned settlement, and eventual retreat.

By Rømer’s own description, the campaign failed to achieve decisive objectives. Yet later writers selectively extracted fragments and reframed this failed expedition as evidence of conquest and dominance.

What’s striking isn’t just that these sources are flawed—it’s that their flaws were rarely questioned. Other evidence forms (Dagbon oral traditions, political chronology, institutional continuity) were sidelined or ignored.

Read Also: African History and Colonial Historiography – Academic Analysis

Karl Haas and the Evidence Against Conquest

Rigorous Source Criticism

The most serious challenge to the Asante Dagomba War narrative comes from historian Karl Haas, who applies careful source criticism to long-accepted claims.

Haas asks a fundamental question: what evidence is required to prove conquest? Rather than assuming Asante dominance and seeking confirmation, he examines each source on its own terms, testing internal consistency against chronology, geography, and political context.

The “GhGh” Problem Resolved

Haas demonstrates why treating “GhGh” as Yendi is weak. Elsewhere in the same manuscript, Yendi is written clearly by name. If the author intended to reference Yendi, why abandon the established spelling?

The description may actually fit Ghobagho, a town near Daboya, rather than Yendi. This alternative identification resolves the linguistic ambiguity and removes the central pillar supporting conquest claims.

Once this ambiguity is acknowledged, the Kitāb Ghanjā cannot be used as firm evidence that Asante forces captured Yendi.

Reading History from the Periphery

Haas’s approach treats Dagbon as a historical actor in its own right, with its own institutions and interests—not merely a passive space affected by southern power.

When Dagbon’s political continuity, succession patterns, and economic life are taken seriously, long-term subjugation becomes impossible to sustain.

Read more: Learn more about Dagbon political structure

Chronology Exposes the Impossibility of Conquest

The Osei Tutu Problem

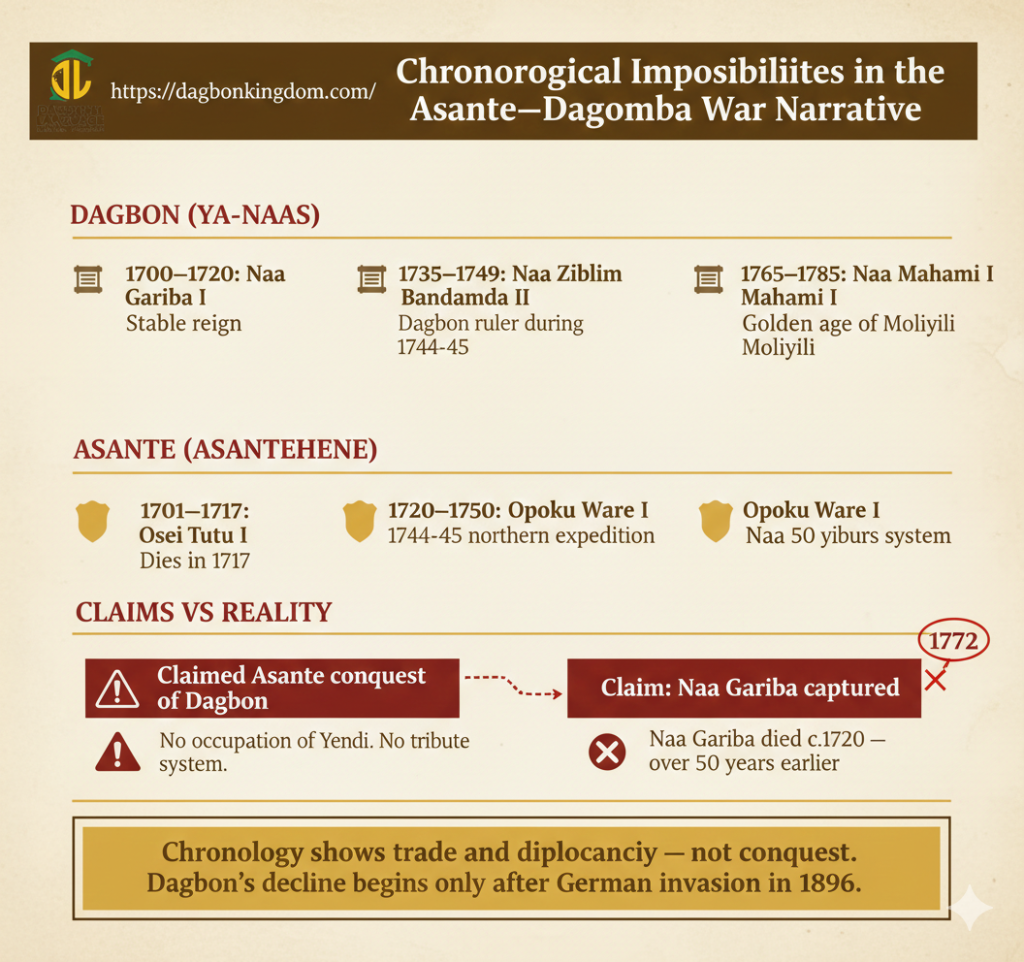

One of the most effective tests of historical claims is simple chronology. When applied to the supposed Asante Dagomba conflict, the narrative collapses immediately.

Osei Tutu I died in 1717—firmly established in both Asante oral history and European records. Naa Gariba I reigned from approximately 1700 to 1720, overlapping with Osei Tutu’s reign for roughly seventeen years.

This entire period is remembered in Dagbon traditions as one of political stability, trade expansion, and diplomatic engagement—not invasion or occupation.

There is no chronological window in which Osei Tutu could have conquered Dagbon. Claims that “Osei Tutu conquered Dagbon” rest on chronological negligence, not evidence.

The 1744-45 Mismatch

The most frequently cited date for supposed conquest is 1744-45, during Opoku Ware I’s reign. By this time, Naa Gariba had been dead for over two decades. The reigning Dagbon ruler was Naa Ziblim Bandamda II.

Yet popular accounts continue linking this campaign to Naa Gariba—revealing persistent confusion of reigns and serious historical inaccuracy.

Even when correctly placed under Opoku Ware I and Naa Ziblim Bandamda II, evidence doesn’t support conquest claims:

- No occupation of Yendi occurred

- No Asante administrative presence was established

- No formal tribute system followed

- Dagbon’s political institutions continued uninterrupted

What occurred in 1744-45 was, at most, a limited unsuccessful northern expedition—not kingdom subjugation.

The 1772 Myth

An even more revealing chronological distortion claims Naa Gariba was captured in 1772. This collapses immediately: Naa Gariba died around 1720, meaning he’d been dead over fifty years by 1772.

This error exemplifies genealogical telescoping—where events associated with later rulers are compressed and attached to earlier, more prominent figures.

When correctly contextualized, this aligns with Naa Mahami I’s reign (1760s-1770s) and describes a commercial dispute connected to trade obligations, not warfare.

Trade Debt vs. Political Tribute

Kambon Samli: The Dagbon Perspective

Within Dagbani oral history, obligations linking Dagbon and Asante are consistently described as kambon samli—debt. This distinction is crucial.

Debt implies a contractual relationship entered voluntarily, with repayment expectations but without sovereignty surrender.

Evidence points to active trade involving:

- Firearms and gunpowder (controlled by southern coastal networks)

- Slaves (captured through northern conflicts)

- Kola nuts and commodities (moving along caravan routes)

Dagbon elites entered exchanges creating outstanding obligations. Annual payments are framed not as submission signs, but as repayment under trade agreements.

Dagbon rulers remained on their skins, governed their people, appointed chiefs, and expanded institutions throughout this period—none aligning with tributary state status.

How Colonial Writers Misinterpreted Economic Relations

The shift from debt to tribute occurred under colonial interpretation. British administrators operated within familiar political categories where regular payments signaled hierarchical domination.

Trade obligations were reinterpreted as overlordship proof. Once payments were labeled “tribute,” Dagbon was automatically recast as a subject state.

Yet corresponding evidence was absent:

- No Asante tax officials in Dagbon

- No Asante control over succession

- No permanent garrisons

- No administrative restructuring

The institutional markers of tribute systems were entirely absent. What existed was a negotiated economic relationship—periodically tense but fundamentally commercial.

Read more: West African Trade Networks in the Pre-Colonial Era

Moliyili’s Golden Age: Proof of Dagbon Autonomy

An Intellectual Center Flourishes

Any claim that Dagbon was subdued must confront one central fact: the extraordinary rise of Moliyili, a center of learning flourishing within Yendi’s political orbit during the supposed “conquest” period.

Moliyili was founded in the 1720s as a royally sanctioned intellectual quarter. Scholars were granted land by the Yaa Naa, protected by royal authority, and integrated into administrative and ritual life.

Manuscripts were produced in Arabic and Ajami covering law, theology, medicine, pharmacology, astronomy, and governance. Scholars developed advanced medical knowledge, including eye disease treatments and early inoculation forms.

They were experts in ironworking, textile production, dyeing, paper making, and agricultural management—fields requiring stability, surplus, and organized labor.

Why Conquered Societies Don’t Produce Golden Ages

Historical patterns are consistent: conquered societies don’t experience sustained golden ages. Military defeat, tribute extraction, and external control drain resources, destabilize institutions, and disrupt intellectual life.

Yet Moliyili reached its height precisely during the period described as Dagbon’s “tributary” era. Scholarship expanded, manuscripts multiplied, technical skills deepened, and Yendi’s influence extended across the Oti Valley.

This coexistence of alleged subjugation and undeniable intellectual expansion isn’t merely unlikely—it’s logically incompatible.

Tribute regimes extract surplus outward. Golden ages depend on retaining surplus for internal development. Moliyili’s success stands as strong empirical evidence that Dagbon remained autonomous, confident, and internally driven.

read more: Explore Dagbon’s intellectual heritage

Cultural Exchange Without Domination

Kambonsi Warriors: Adaptation, Not Occupation

The kambonsi warrior tradition and kambon-waa music are often cited as proof of Asante dominance. In reality, they demonstrate the opposite.

While certain elements have Asante origins, their meaning, structure, and performance are firmly embedded in Dagbon society. Dagbon controls:

- The ritual context of performance

- The language of praise and command (primarily Dagbani)

- Political authority under which kambonsi operate (answering to Dagbon chiefs and the Yaa Naa)

If Asante had conquered Dagbon, Asante military institutions would remain dominant and intact. Instead, they were reworked, localized, and subordinated to Dagbon political culture.

Linguistic Evidence of Autonomy

Language provides further clarity. Several Dagbon military terms derive from Twi expressions:

- Asafohene becomes Sapashini

- Yɛn kɔ bɔ tuo (“let us go and fire guns”) becomes Panpantua

These transformations reflect a common cross-cultural process: foreign terms are reshaped to fit local phonology and usage.

In conquest cases, conquerors impose their language with minimal alteration. What we see in Dagbon is the reverse—borrowed terms are absorbed, reinterpreted, and made Dagbon. This signals agency and control, not submission.

What Real Conquest Looked Like: 1896

The German Invasion Benchmark

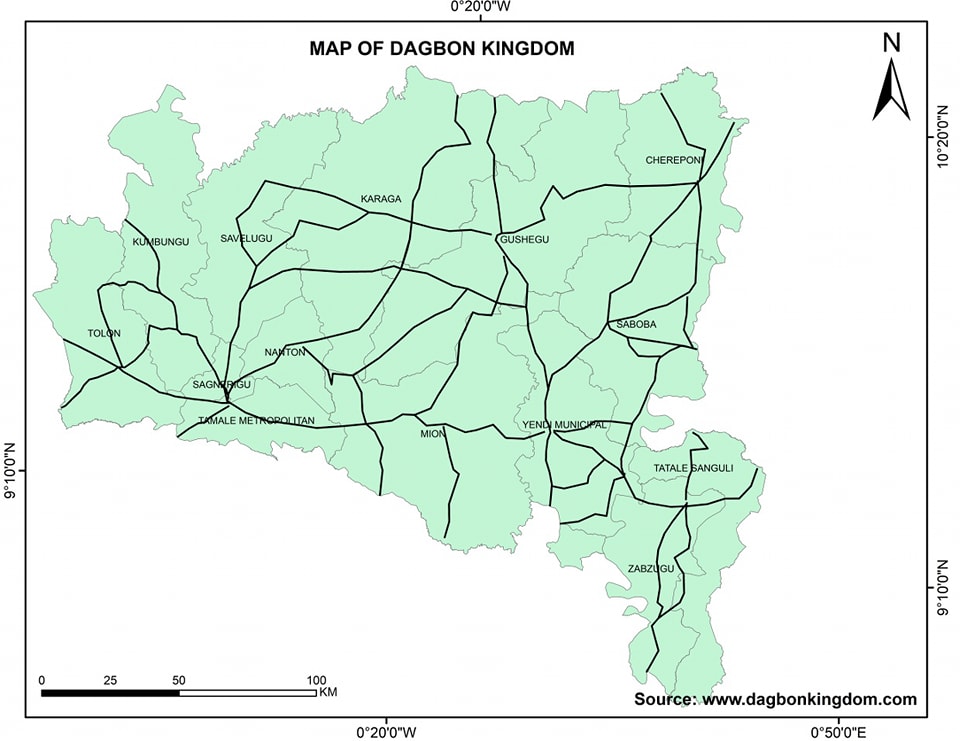

If “conquest” is to have real meaning, it must be grounded in observable outcomes. Dagbon’s history provides a clear benchmark: 1896, when German colonial forces invaded.

German forces met the Dagbon army at Adibo. Unlike ambiguous 18th-century campaigns, this ended in clear military defeat. The outcome was immediate and devastating:

- Yendi was burned

- Manuscripts were seized and destroyed

- Population collapsed dramatically (nearly half)

- German authority replaced Dagbon sovereignty

- The Yaa Naa’s authority was subordinated

This is what conquest looks like: defeat, occupation, loss of autonomy, and systematic destruction.

Why Earlier Relations Don’t Qualify

When concrete 1896 conquest markers are applied to earlier Asante Dagbon relations history, they fail every test:

- No decisive military defeat comparable to Adibo

- Yendi was never occupied or destroyed by Asante

- The Yaa Naa was never removed

- Dagbon’s political institutions continued functioning

- Succession proceeded according to internal norms

Earlier Asante-Dagbon relations reflect interaction without domination, influence without control, and negotiation without sovereignty loss.

The comparison with 1896 sharpens the central argument: Did Asante conquer Dagbon? No. Dagbon was conquered—briefly and tragically—by European colonialism, not by Asante.

The True Nature of Asante-Dagbon Relations

Once conquest myths are set aside, a more historically grounded picture emerges. The Asante Dagbon relations history was asymmetric but mutually beneficial, shaped by geography, resources, and regional politics.

Asante, positioned closer to coastal trade, held advantages in military technology and firearms access. Dagbon, controlling northern trade routes and anchored in Islamic scholarship, held economic and intellectual power.

Their interaction was defined by:

- Active trade partnerships

- Diplomatic negotiations

- Cultural exchange and adaptation

- Occasional military tensions

- Mutual respect between powerful kingdoms

Cultural forms crossed boundaries but were adapted and controlled by Dagbon institutions. The Yaa Naa and Dagbon chiefs remained ultimate authorities.

Crucially, there was no long-term military subjugation. Dagbon was never reduced to an Asante province, never ruled by Asante officials, and never stripped of sovereignty.

What existed was a negotiated relationship between two powerful African states, each pursuing interests within a shared regional system.

Conclusion: Reclaiming Historical Accuracy

The Asante Dagomba War resulting in Dagbon’s conquest is best understood as historiographical invention, not established fact. It arose from colonial assumptions, selective source reading, and failure to test claims against chronology and institutional evidence.

When the record is examined carefully, dates, political continuity, and material evidence all contradict conquest claims. Dagbon didn’t experience military occupation, administrative takeover, or cultural destruction at Asante hands.

Restoring this history matters because it:

- Reclaims Dagbon agency as an active, autonomous historical actor

- Corrects colonial distortions with evidence-based analysis

- Enriches African historiography by acknowledging complexity over simplification

Moving beyond the Asante Dagomba war myth doesn’t diminish either society. Instead, it honors both by presenting their past as it truly was—a history of power, negotiation, exchange, and resilience grounded in African realities rather than colonial imagination.

The question “Did Asante conquer Dagbon?” can now be answered with confidence: No. What existed was a complex relationship between two sophisticated kingdoms that maintained their sovereignty while engaging in trade, diplomacy, and occasional conflict—the true nature of precolonial African statecraft.

Sources and References

Primary and Scholarly Sources

- Haas, Karl. A Re-Assessment of Asante–Dagbamba Relations in the Eighteenth Century.

Unpublished academic dissertation.

(Critical reassessment of the alleged Asante conquest of Dagbon, with detailed source criticism of Arabic and European accounts.) - Wilks, Ivor. Asante in the Nineteenth Century. Cambridge University Press.

(Context on Asante expansion, political structure, and limits of imperial control.) - Bowdich, T. Edward. Mission from Cape Coast Castle to Ashantee (1819).

(Eyewitness observations of Kumasi and references to Yendi’s size, trade, and regional importance.) - Rømer, Ludwig Ferdinand. A Reliable Account of the Coast of Guinea (18th century).

(European account often cited in conquest narratives; used here critically and in full context.) - Oral traditions of Dagbon (Dagbamba historians, elders, and royal traditions).

(Referenced comparatively, not treated as literal chronology.)

Dagbon Intellectual History

- Exploring the Golden Era of Dagbon Kingdom (Moliyili documentation).

Dagbon Media Foundation archives.

(Details on Moliyili as an intellectual, medical, and administrative centre of Yendi.) - Dagbon oral–historical accounts on Moliyili, Kamshegu, and Oti Valley mosques.

Chronology and Ruler Lists

- List of Dagbon Kings (Ya-Naas) – Wikipedia

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ya-Naas_of_Dagbon - List of Asante Kings (Asantehene) – Wikipedia

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Asantehene

(Ruler lists used strictly for chronological cross-checking and reign alignment.)